Hello, reader.

This letter takes roughly five hours to write & edit & record each week. I’m saving any spare pennies & pounds I earn from it to study & enter short story competitions — this week, though, any money raised will be donated to Alzheimer’s Research UK (or you can donate here directly).

If you like what I do, please support me: subscribe (for free or a few quid), forward this letter to a friend who might like it, comment at the end, buy me a coffee, a book, one-off PayPal me, or hire me and let’s work together.

Thank you — Daniel.

Hello,

Here are ten things I’d like to remember from the past week.

one

unforgettable

in every way

& for evermore

that’s how you’ll stay

From Unforgettable by Nat King Cole.

but I believe in love

& I know that you do, too

& I believe in some kind of path

that we can walk down, me & you

so keep your candles burning

make her journey bright & pure

that she’ll keep returning

always & evermore

into my arms

From Into My Arms by Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds.

Tiger got to hunt, bird got to fly;

man got to sit and wonder ‘why, why, why?’

Tiger got to sleep, bird got to land;

man got to tell himself he understand.

From Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut.

two

In my mid-twenties, imploding from the pressures of managing a bookshop in London, I took a couple of weeks off to travel here & there across one of my childhood homes, the Isle of Wight. My grandparents on one side (dad’s, in Lake / Sandown), uncle & aunt on the other (mum’s, in Ryde), live there.

By bus & hike, I explored.

Often, as is my way, my phone would die.

I’d strand myself daily in the middle of the countryside — no music (podcasts & audiobooks would come a few years later, at the start of the pandemic), no photos, music, maps, nor any calls to taxis, pleas to the family, or bus routes / times to check. (I once waited 20 minutes at a stop, accepting my fate to wait up to an hour for something to turn up, only to be told by a kind & painfully amused passer-by that the stop, nay the route, hadn’t existed for at least three years. Less than two minutes after I walked away, an old bus coughed & rambled by me; my stubborn chase was unsuccessful.)

I was often trapped; I hitched lots of rides.

One sunny day, after visiting the National Trust site of St Helens Duver (‘a sandy spit of land on the eastern tip of the Island, rich in wildlife & history’), I wandered up to Kevars Cafe in the Country (‘Winner of Best Breakfast award from Isle of Wight Radio Awards: Best in Business 2020’), dead phone in hand.

While eating (as if I was famished, I remember — I’d also neglected breakfast, and it was now 1pm), a woman whose face I’ve forgotten — barely 5ft tall, dark hair, kind & wild — shouted over to me: What’s that yer readin’, then?

The Original Ghosts of the Isle of Wight by Gay Baldwin had been recommended to me by the author of Wolf Brother & Wakenhyrst, Michelle Paver — we’d recently met while promoting the latter book, and briefly kept in touch through letters. In a caffeinated conversation I can’t fully remember, both my family’s roots in the Isle of Wight and my love of ghost stories had come up. She’d recommended Baldwin’s series of self-published ghost stories (&, as there hadn’t been a new issue in years, she wondered & asked me to find out whether the author was still alive).

The woman who had shouted to me across the cafe knew what I was reading, it turned out — she & Gay (very much alive) were friends, possibly cousins but I may be misremembering that, too. We chatted for a moment, I shamelessly asked where & when she was headed next, and I hitched my next ride.

I pressed Q on her friend’s / cousin’s work with ghosts (I forget Q’s real name — I just know it was unusual, and the letter Q lends a boundary-crossing shape to this memory, a line landing both in & out) — they’d visited demented ruins & ancient buildings & held seances on abandoned hospital sites. The idea of ‘thin places’ was presented to me for the first time: where our world & that of ‘the next’, the one we go to when we die, or simply exists in parallel, could be traversed, stepped through.

We discussed our own theories. Had I ever seen a ghost? Yes, I think so. Hazy childhood memories, some supplementary stories from (mostly) sensible people (thanks, mum), and another from my early 20s. Much like the dream I described last week, how real it had felt, I recalled a dream I’d had the night after someone very close to me had died — young, suddenly — soon after we’d graduated from university. I was certain she’d visited my dream, spoken with me, said goodbye. I woke, smothered by an intense acceptance & sadness, suddenly certain of my swift departure from unchallenged atheism & my newfound, glorious freedom in uncertainty about what goes on when someone dies.

Q’s mother — &, I suppose, the people around her — had struggled with dementia for years, and that’s where she was headed now, passing through Ryde about 20 minutes walk from my aunt & uncle’s cottage where I was staying. She loved her mum but hoped for a ‘quick death’ — this dementia was a slow, drudging, stubborn, confused death, and Q would never be ready to be forgotten.

I tentatively mentioned my nan. She had been diagnosed just a handful of months before with early stages of dementia, soon replaced with Alzheimer’s. Dementia felt like one of those ‘thin places’, then, I remember saying: dead & alive, here & not; renewed love & newfound pain. It was like a spinning-top, furiously spinning for 80 years, was slowing & readying to teeter — but it hadn’t yet, and I could see the grain of its wood as some invisible hand turned it manually.

‘Ghost’ expanded as an idea for me. Words have smudged & twisted a little in the passing years, but the conversation in the car with Q will remain with me forever.

three

(Capital letters & grammar were edited without consulting. It bugs me still, but so it goes.)

Published in 2015, I’d written this mostly, furiously, after Christmas dinner: nan, sat at the dinner table, was being talked about, around, like she’d already died or was a prop in the room, meant only to inspire some contemplation of life for everyone else. She looked bewildered.

Whether the sentiment behind it was understood by my family at the time, I don’t know — I worried that my nan would be ironically forgotten in all this, like the loss of her memory was a vacuum, a black hole, pulling in the minds of those around her. She was still here, here, right here, I wanted to say.

Grandad probably just loved that I’d followed through on my lamentations of being a writer one day for once, so he sent it to the local paper.

four

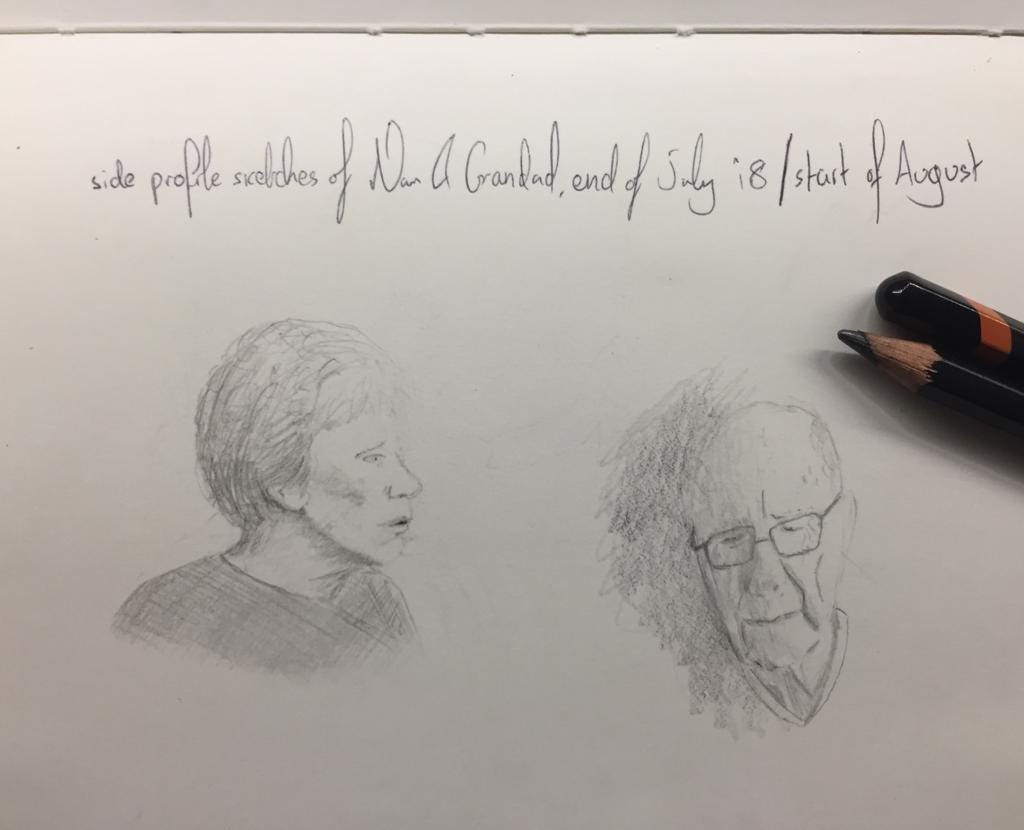

Nan’s diagnosis also inspired a spell of drawing a few years later.

I started exploring my grandparents’ lives more, on both sides of the family, asking questions, visiting their childhood homes in London, even finding records for my other nan’s father that proved he hadn’t died when she thought he had.

I’d spend hours on these inch-by-an-inch drawings. My partner at the time joked about how small they were, encouraged me to try & cover larger spaces, but I think — much like running — it may have started with the curiosity of learning how to do something new, but it was the intensity of focus that took over, kept me going, like I was passing through all the usual noise in my head to this eye of a storm and would feel at peace there, finally, in that small square in front of me.

The images of my grandparents above are young & joyful, then older & in moments of despair (we’d just been walking along the coast near their home, so they were probably just a bit pooped). I’m not sure which I drew first, whether it matters, but they both occupy the same space, the nan & grandad section of my brain.

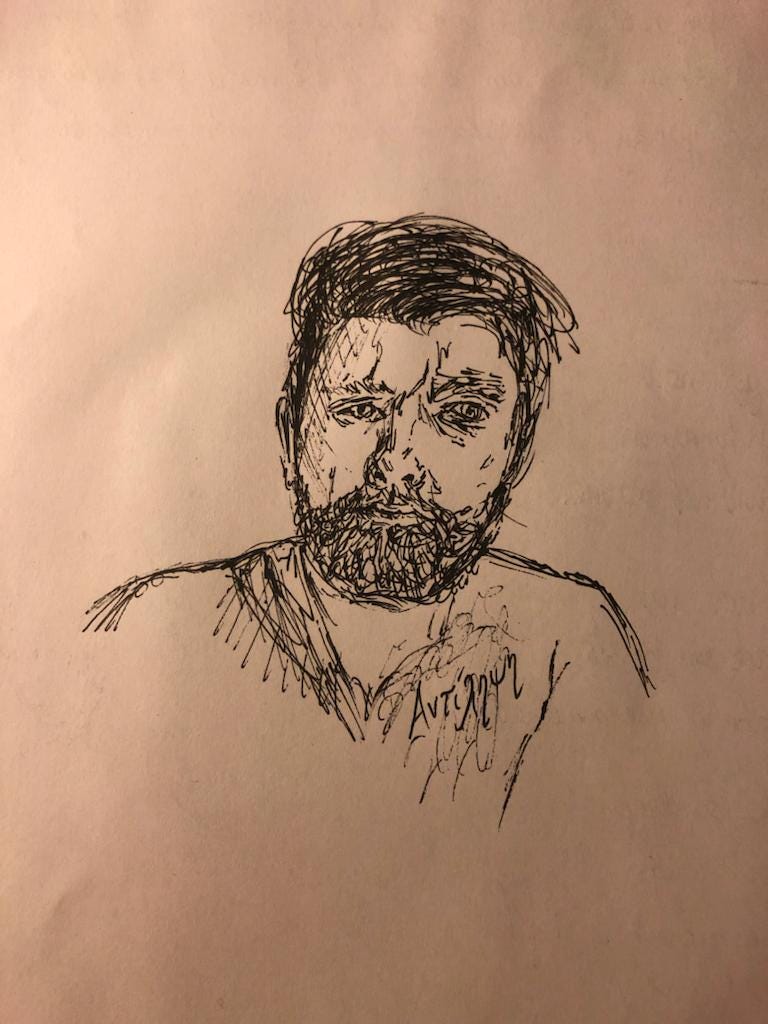

My self portrait, below, was also from the night after that Christmas dinner, where I felt far too much change.

five

Elizabeth Margaret Kelly, my nan, died peacefully in Wellow Unit at St Mary’s Hospital on the Isle of Wight, minutes after midnight on All Hallows’ Eve.

She was a friend, wife, mother, grandmother, sister, neighbour, nurse; ‘hello, me’ & ‘doesn’t it go quiet when we’re eating’ & ‘ooo I love a good murder’. She was kitkats & wet cakes; thick hair & thimbles; Harry Potter & Eastenders; small hugs & spry energy; garden flowers & cigarettes; safety & mischief; kind & no-nonsense; lavender & smoke; grace & glory.

She forgot my name only once, at my sister’s wedding, and she gave me a hug anyway. I saw her beaming with so much joy during the service, and, for me, she decimated the idea that someone loses the rest of their life at the start of that diagnosis.

She had grandad by her side when she died; mum tells me he’d been singing Unforgettable on her visit, holding her hand as she slept.

She was cheated from the untarnished, untouched life she deserved.

She was gifted with a long, happy life, and a peaceful death. She was so loved.

She is unforgettable, and still here, always.

six

I wanted to explore cultural takes on thin places to unveil my own: times & places & events where the world as we see it around us is separated from another world by barely a sheet of tissue paper. I think it’s because I’d like to understand better why they’re never really ‘gone’. The list, which you’ll find me working on here, currently includes:

Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies by Maddie Mortimer — I’m quarter of the way through this story, flitting between the perspective of cruel, cold cancer, its host person, and the people around her. Disease manifested or personified brings it closer to me, perhaps inaccurately but at least visibly or at all for the first time. It’s what I did with nan’s Alzheimer’s years ago: some of the physical effects on the brain are the loss of neuronal connections (chasms & canyons), neurofibrillary tangles (dark forests & thickets), amyloid build-up and vascular problems (toxic salt flats). In Mortimer’s book, language bounds madly & swells out of the page, like Porter’s Lanny, and the regular titles of each scene, like Zusak’s The Book Thief, give weight to small conversations, a fractured, splintered life to add the sense of fast, uncontrollable pace.

Thin Places by Kerri ni Dochartaigh

The Many Worlds of Albie Bright by Christopher Edge — Something to do with a young boy with a dead mum, who learns that because of the distance of planets & speed of light, that something in the sky right now

The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupery

Any others? Throw them my way — thank you.

seven

While looking into Hallowe’en (or: All Hallows’ Eve, squished into one), I found the folklore behind our grinning, firey pumpkins.

Heading home after a night of drinking, a man named Jack encounters the Devil & tricks him into climbing a tree. Quick-thinking Jack etches the sign of the cross into the bark, thus trapping the Devil, then strikes a bargain: Satan can never claim Jack’s soul. After a life of sin, drink, & mendacity, Jack is refused entry to heaven when he dies. The promise kept, he’s also refused entry into hell. The Devil throws him a coal straight from the fires of hell. It was a cold night, so Jack places it in a hollowed-out turnip to stop it from going out. Since that time, Jack and his lantern have roamed, looking for a place to rest.

In Ireland & Scotland & christianity, this jack-o’-lantern folktale is said to represent souls denied entry to both heaven & hell — although, traditionally, they used turnips. Immigrants to North America used the native pumpkin: softer & larger & easier to carve (& they better match an autumnal wardrobe).

eight

My chiropractor, in our first ever session, explained that the cracking sounds & subsequent euphoria I’d been lured in by (thanks, TikTok) were no cause for concern — it wasn’t onset arthritis, nor bones being juggled & shifted.

The crack was a release of air, pressure, between bones & joints. The space would creak open, release the air, and fill that space with synovial fluid, to cushion the ends of bones & reduces friction when moving. Greater mobility, less pain, caused by short, sharp moments. There’s a metaphor in there somewhere.

nine

These are a few songs I’ve reached for in moments of loss.

Mad Rush by Philip Glass

Whatever Lets You Cope — Fleet Foxxes

We Have All the Time in the World — Louis Armstrong

The rest are on my down & out playlist.

When I’m anxious, I do what I can to escape the feeling. There’s little-to-no reading, just comfort viewing & listening & anything sensory that pulls me along with automatic momentum. I do whatever I can to get away.

When I’m low, I often read & listen & watch to feel it fully, not just visit. It’s ‘safer’ than my nerves, and brings a level of contemplation I enjoy — or, at least, it’s a feeling I dislike being directed somewhere other than at myself.

Before nan died, I was low, for no identifiable reason other than a hiccup in the hormonal soup soaking my brain. Nan’s death, of course, made that worse but in a different way — one where I can pair immense sadness with a drive to understand.

ten

I’ve updated my website’s to do page with everything to get done, including to write & deliver a eulogy for my nan later this month.

Thank you for reading.

Please support my writing: subscribe (for free / a few quid), forward this letter to a friend who might like it, comment at the end, buy me a coffee, a book, or PayPal me as a one-off. We could also work together.

This week, any money raised will be donated to Alzheimer’s Research UK (or you can donate here directly).

Have a lovely day — Daniel.